We've just about lost the fish. In fact, if we were to count the cost of the fish-permit buybacks and the litigation and the failed hatcheries and all the process that has followed the Boldt decisions, we have probably spent more money on "not losing" the last of these fish than we spent putting astronauts on the moon. And the fact that you can often buy the flesh of an endangered species in the supermarket for less than you pay for cheese, is at least deeply ironic.

In fact, it seems every bit as absurd as buying gasoline at the pump for under $10/gallon when we are spending $100,000/minute in an even less effective effort to control the world price of oil.

So, we need to ask ourselves, and one another: what is really going on?

I am going to tell you that the reason that these particular fish are having more trouble now than they had after the glaciation, when the place was about as habitable as a supermarket parking lot, is twofold:

Because we - them and us - have a lot in common. We are really top-of-the-food-chain predators and we are both "opportunivores" - that is to say: we eat anybody smaller or slower or dumber than we are for dinner, and not only that they taste good and are full of stuff that is hard to find elsewhere, and we really like to eat them.

So problem #1 is that we did not look at them in terms of their "functions and values " in the ecocsystem - we looked at them as a limitless supply of free food and hunted them w/o mercy.

But it now appears that a problem at least as serious as overfishing is that we have each gone blindly after the same physical territory. And right or wrong, we are cleverer than the salmon, and so we have been winning consistently in our own efforts to develop and maintain our nests in and along their rivers for about 100 years. That does not mean we are wiser, but we are clever certainly.

But very few of us have even considered the disproportionate consequences of our actions until quite recently. The huge advantage we have over them, at least for the moment, is that we can easily move out of their way, but they really can't move out of ours.

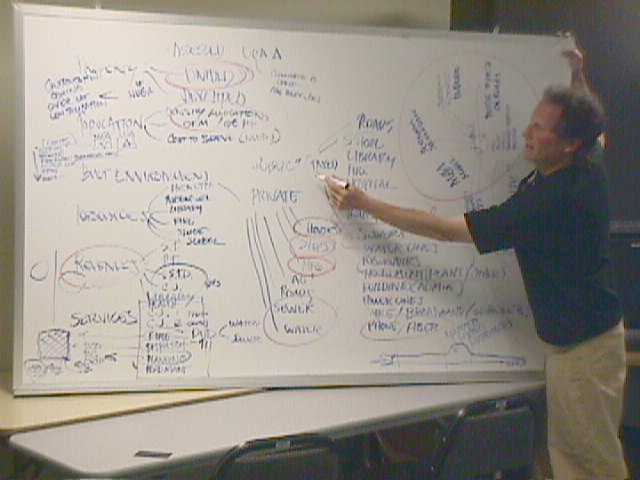

This image does not completely communicate the issues, because it does not really show the hydrograph - the fluctuating amount of water in the rivers. But it does an excellent job of showing who is in the river, and when they are there. But it is still very useful because we can easily run it against the hydrograph.

It does not really geolocate the spawning gravels of the different species, either. And there is the rub, because these are fish who have "co-evolved" with the streams to effectively utilize every accessible reach of the stream, and we have substantially changed the lower reaches, with outright barriers to fish passage and by diking.

These two images from the Dungeness River illustrate the precise nature of the problem. When river channels narrow, the water accelerates. At higher velocity it moves more and larger cobbles. When the channelizing is past - in this case the dike and the bridge, it slows and drops the payload of gravel it was carrying, locally raising the level of the bottom of the stream. During periods of low flow, this elevated bottom presents obstacles to fish passage, and if fish foolishly spawn in these gravels (as they have done very successfully for the past hundred centuries) when there is clearly adequate flow, their nests may very well dessicate when the flow goes subterranean - and most of the water in the river is running subsurface, through the gravel.

No comments:

Post a Comment